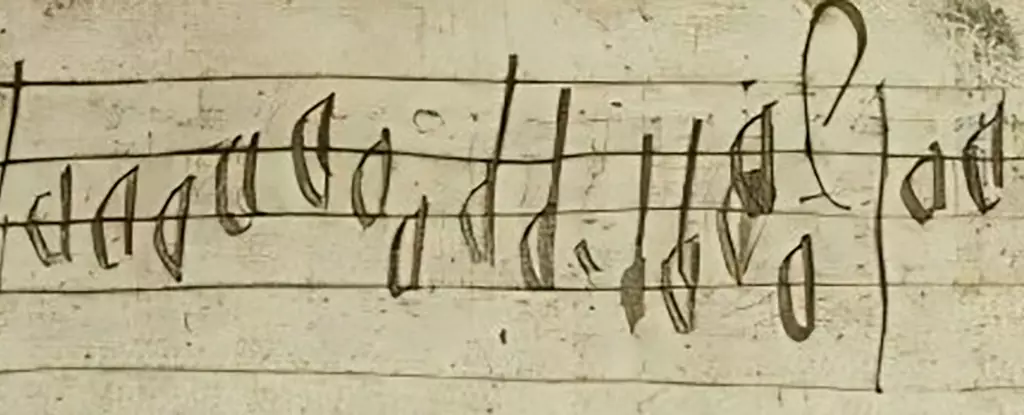

The journey of music through time is akin to a time machine, capable of unearthing emotions and memories suppressed by the inexorable passage of years. Recent investigations into Scotland’s musical history have yielded a remarkable find: a short segment of sheet music dating back to the 16th century. This 55-note treasure hints at a vibrant musical culture that has all but evaporated, leaving behind few remnants. The fragment in question was discovered nestled within the historically significant Aberdeen Breviary, a tome considered to be Scotland’s first printed book, published in 1510.

The Aberdeen Breviary is more than just a collection of prayers, readings, and hymns; it symbolizes the religious and cultural landscape of early 16th-century Scotland. Although contemporary readers may not recognize this work, it played a pivotal role at the dawn of the Scottish print industry. It serves as an artifact of its time, making the recent revelation of a musical fragment within its margins all the more significant. Researchers from KU Leuven and the University of Edinburgh have made it their mission to analyze this treasure trove that, despite its diminutive stature, has immense cultural implications.

The musical notation discovered within the book points to the hymn “Cultor Dei, memento” (“Servant of God, remember”), a piece of polyphonic music that has managed to endure in modern Anglican services during Lent. This survival is remarkable given that the Reformation obliterated many musical practices from Scotland’s sacred traditions. It is thrilling to think about the connections this hymn may create between the past and present, resurrecting tunes that may have been forgotten for centuries.

The musicologist David Coney from the University of Edinburgh has articulated the significance of this discovery poignantly. He notes that from a single line of music, scholars can resurrect hymns that have lain silent since the Renaissance. Notably, the discovery raises the tantalizing possibility of reconstructing additional harmonies that would have accompanied the hymn, bridging centuries of silence with a melodic resonance.

Despite the lack of contextual information such as attribution or a title associated with the discovered notation, researchers have identified its polyphonic nature. This compositional style reflects a musical sophistication that challenges the long-held narrative that pre-Reformation Scotland lacked a rich sacred music tradition. Another musicologist, James Cook, emphasizes that evidence of high-quality music-making existed in Scotland’s religious institutions, countering the narrative of aridity in Scotland’s pre-Reformation liturgy.

The implications of this find extend beyond mere historical curiosity; it challenges perceptions of Scotland’s musical past and opens new avenues for exploration. The history of the Aberdeen Breviary and its connections to significant locales like Aberdeen Cathedral are crucial in contextualizing this musical fragment. However, the identities of the individuals who authored this notation remain cloaked in mystery.

Such uncertainties do not diminish the importance of the discovery. On the contrary, they invigorate the pursuit of further research. Scholars are now inspired to sift through other similar texts and books, meticulously examining margins and blank pages for additional musical fragments. Paul Newton-Jackson, another musicologist involved in the project, posits that hidden treasures may still lie undiscovered in the collections scattered across Scotland’s libraries and archives.

This examination of a 16th-century musical fragment is emblematic of the larger narrative of recovering lost cultural heritage. As musicologists delve into the remnants of Scotland’s liturgical past, they provide a voice to an era that may have otherwise been forgotten. The journey of this rediscovered hymn mirrors the broader quest to reestablish cultural ties that bind the present to the past.

In sum, the resurgence of interest in Scotland’s ecclesiastical music symbolism reflects a revivalist spirit eager to explore and reclaim lost melodies. Whether as educators, performers, or listeners, we now have an opportunity to immerse ourselves in a soundscape previously silenced by time. The importance of music as a time capsule cannot be overstated, for it continues to resonate with the humanity embedded in its creation, waiting to be rediscovered.

Leave a Reply