The potential association between antibiotic use and cognitive decline, particularly dementia, has elicited significant interest in the medical community. Recent findings from a comprehensive study conducted over a period of 4.7 years indicate no direct link between antibiotic usage and dementia in a select group of healthy older adults. However, the implications of these findings are nuanced, suggesting that caution is warranted before applying the results to broader populations.

Conducted by Andrew Chan, MD, MPH, and his associates at Harvard Medical School, the study evaluated 13,500 participants aged 70 and above enrolled in the ASPREE (Aspirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly) trial. The primary aim was to investigate whether the usage of antibiotics over nearly five years could be correlated with an increased incidence of dementia or cognitive impairment. The research revealed that antibiotic users exhibited a comparable risk of developing dementia (Hazard Ratio [HR] 1.03, 95% Confidence Interval [CI] 0.84-1.25) and mild cognitive impairment without dementia (HR 1.02, 95% CI 0.94-1.11) in comparison to non-users.

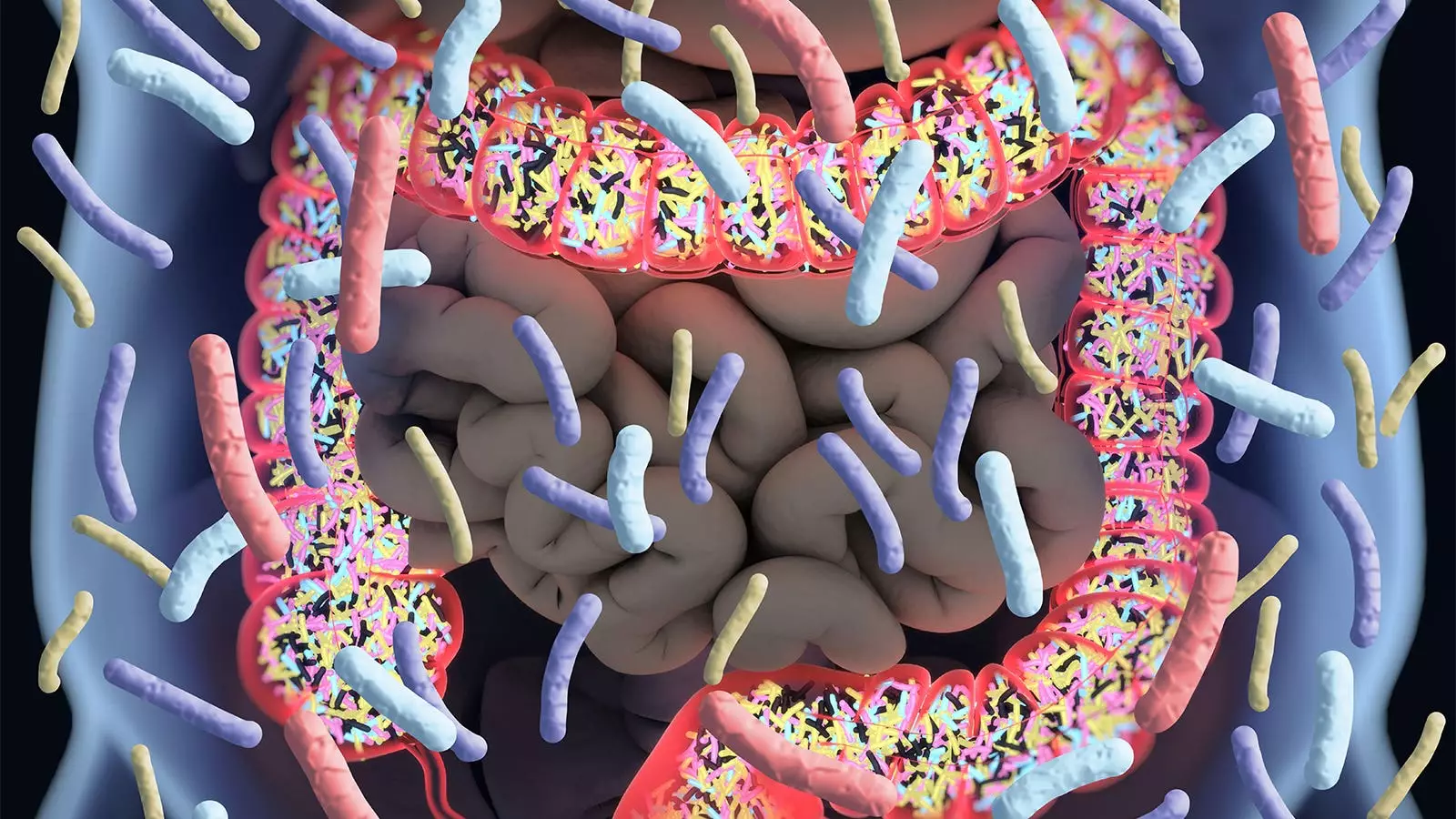

This data insinuates that among a relatively healthy cohort, antibiotics may not pose a detrimental effect on cognitive function. Nevertheless, the study also highlighted that the disruption of gut microbiomes—often a consequence of antibiotic use—remains a concern, given the established connection between gut health and overall brain function. Chan emphasized the importance of these findings, stating that for older adults, concerns about cognitive decline due to antibiotic prescriptions might be unwarranted.

However, while the outcomes are indeed reassuring for healthcare providers prescribing antibiotics to healthy older adults, there are significant reservations. An accompanying editorial by Wenjie Cai, MD, and Alden Gross, PhD, from Johns Hopkins University raises critical questions regarding the generalizability of the findings. The participants in ASPREE were specifically selected for their health status, being free from serious disabilities, cardiovascular events, and other severe illnesses. This careful selection means that the results might not accurately represent the broader older population, including those who may have pre-existing health issues or comorbidities.

Previous studies have drawn mixed conclusions regarding antibiotics and cognitive health. For example, the Nurses’ Health Study II suggested that women with significant antibiotic exposure in midlife exhibited lower cognitive scores seven years later. The juxtaposition of these findings with the current study highlights the complexity and variability of research on this subject, underlining the necessity for further exploration.

To contextualize these findings, it’s essential to delve into how antibiotics function within the human body. Antibiotics can significantly alter the gut microbiome, leading to potential long-term health effects. Given that the composition of gut bacteria plays a crucial role in neurological health, any disruptions could potentially lead to cognitive issues over time. Although the current study indicates no immediate risk, further longitudinal analyses will be critical to understanding the longer-term ramifications of antibiotic use, especially in populations that are not as healthy as the ASPREE cohort.

Additionally, Chan and his colleagues have acknowledged the limitations surrounding their research. The reliance on filled prescription data may not provide a full picture of actual antibiotic use, and potential confounding factors could skew the results. These elements contribute to the necessity of interpreting the findings with caution.

While the findings from this extensive study are promising in suggesting that antibiotic use does not correlate with increased dementia risk in healthy older adults, they also underline the importance of approaching this issue with a critical lens. The interplay between antibiotics, gut microbiome health, and cognitive function remains a compelling area for future research, particularly among diverse and varied populations. As the landscape of healthcare evolves, understanding these relationships will be essential for informing clinical practices and ensuring the cognitive health of older adults. Thus, future studies must aim to bridge the gaps in knowledge and provide a clearer picture of how antibiotic use might influence long-term cognitive health across different demographics.

Leave a Reply