The burial practices of early Homo sapiens and Neanderthals offer a compelling window into the social and cultural dynamics of our prehistoric ancestors. Emerging evidence suggests that these long-extinct human species began to bury their deceased approximately 120,000 years ago in the Levant region, a finding that underscores the potential for cultural exchanges and common practices between them. Recent academic inquiry has delved into the ways both groups honored their dead, revealing intriguing similarities and notable differences that may offer insights into their relationships and daily lives.

Burial rituals signify a complex understanding of life and death, and the convergence of Homo sapiens and Neanderthals burying their dead indicates a significant cultural phenomenon. The archaeological findings suggest that these practices may have originated in the Levant before spreading to other regions, such as Europe and Africa. Researchers from Tel Aviv University and the University of Haifa have meticulously cataloged burial sites from both groups, providing a comprehensive overview of the excavation. This highlights a possible shared tradition, alluding to a broader cultural landscape in which both species coexisted, interacted, and possibly influenced each other.

This period marked a pivotal point in human evolution, not just in biological terms but also in cultural expression. The hypothesis presented by the researchers posits that the rise of burial practices corresponds with heightened competition for resources as both groups populated the same geographical area. Such competition could have fostered a sense of communal identity, which was manifested through shared burial rituals, regardless of the underlying motivations.

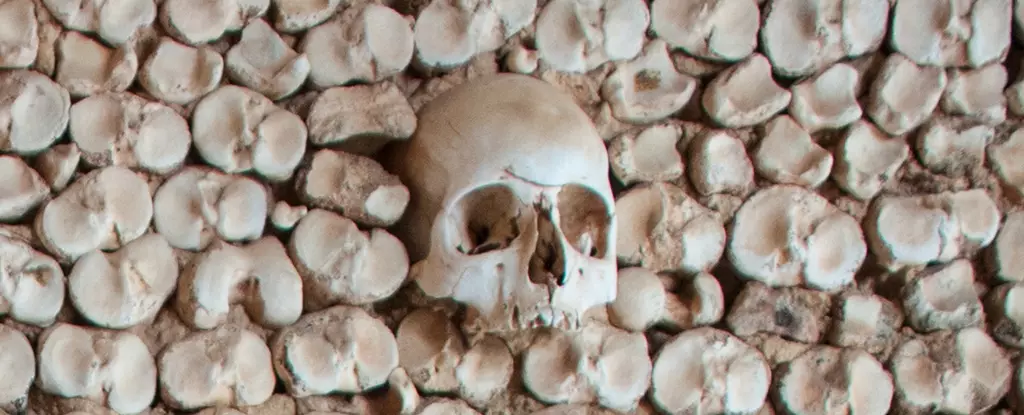

In their study, the researchers differentiate between purposeful burials and natural processes affecting skeletal remains, a distinction that is critical for understanding the nuanced nature of these rituals. Among the methods for differentiating these practices were the positioning of skeletons, the presence of grave goods, and evidence of purposeful excavation. Notably, both Neanderthals and Homo sapiens performed burials that included individuals of varying ages, indicating a communal approach to death. However, the notable prevalence of infant burials among Neanderthals may suggest differing societal values regarding age and mortality between the two groups.

As for grave goods, both groups included various artifacts such as animal bones or stones, but the manner and intent behind these offerings exhibited substantial differences. Neanderthals favored deeper burials in caves, perhaps indicative of a connection to their belief systems or environmental adaptations, whereas Homo sapiens chose more exposed locations like cave entrances or rock shelters. The positioning of the skeletons also stands out; while Neanderthals exhibited a more varied arrangement of bodies, Homo sapiens commonly placed their dead in a fetal position, suggesting distinct cultural meanings associated with this posture.

The nature of grave goods provides a fascinating glimpse into the respective worldviews of both groups. Neanderthals appeared to utilize stones in a more functional manner, potentially as markers for burial sites, whereas Homo sapiens’ graves featured ornamental items such as ochre and seashells, suggesting a more elaborate understanding of beauty and memory. Such distinctions imply differing levels of symbolism associated with death and commemoration, reflecting a profound divergence in cultural practices.

The interplay between these burial practices raises questions about social cohesion and cultural identity within and between these species. While some aspects of their material culture were indistinguishable, their burial practices reveal a complex narrative filled with cultural significance and symbolic meaning.

The extinction of Neanderthals around 50,000 years ago catalyzed a dramatic shift in the social fabric of the Levant. Following this extinction event, human burial practices seemed to diminish for millennia, which poses further questions about cultural continuity or adaptation in response to environmental and social changes. The resurgence of burial customs during the late Paleolithic, especially alongside the emergence of the sedentary Natufian culture, might suggest an evolution of these practices influenced by new societal structures and lifestyles.

This exploration into the burial practices of early Homo sapiens and Neanderthals enriches our understanding of human history, illuminating the cultural complexities that shaped their existence. The evidence of shared practices coupled with distinct differences embodies the dynamic interplay between competition and cooperation among early human groups. Each burial site serves not only as a grave but as a repository of cultural heritage, reflecting the sophisticated thought processes of our ancestors through their treatment of death and memory. Further investigation into these ancient practices will undoubtedly continue to reveal the rich tapestry of interactions that defined the human story long before the modern era.

Leave a Reply