Childhood obesity is a significant public health concern that has been steadily increasing over the past few decades. The repercussions of this epidemic are alarming, from rising rates of type 2 diabetes and hypertension to the psychological toll of bullying and social stigma. As a pediatric obesity medicine specialist, I have encountered numerous adolescents struggling with these challenges. My experience has provided valuable insight into current treatment options, especially the potential of GLP-1 receptor agonists, such as semaglutide and liraglutide, in managing obesity.

The Promise of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists

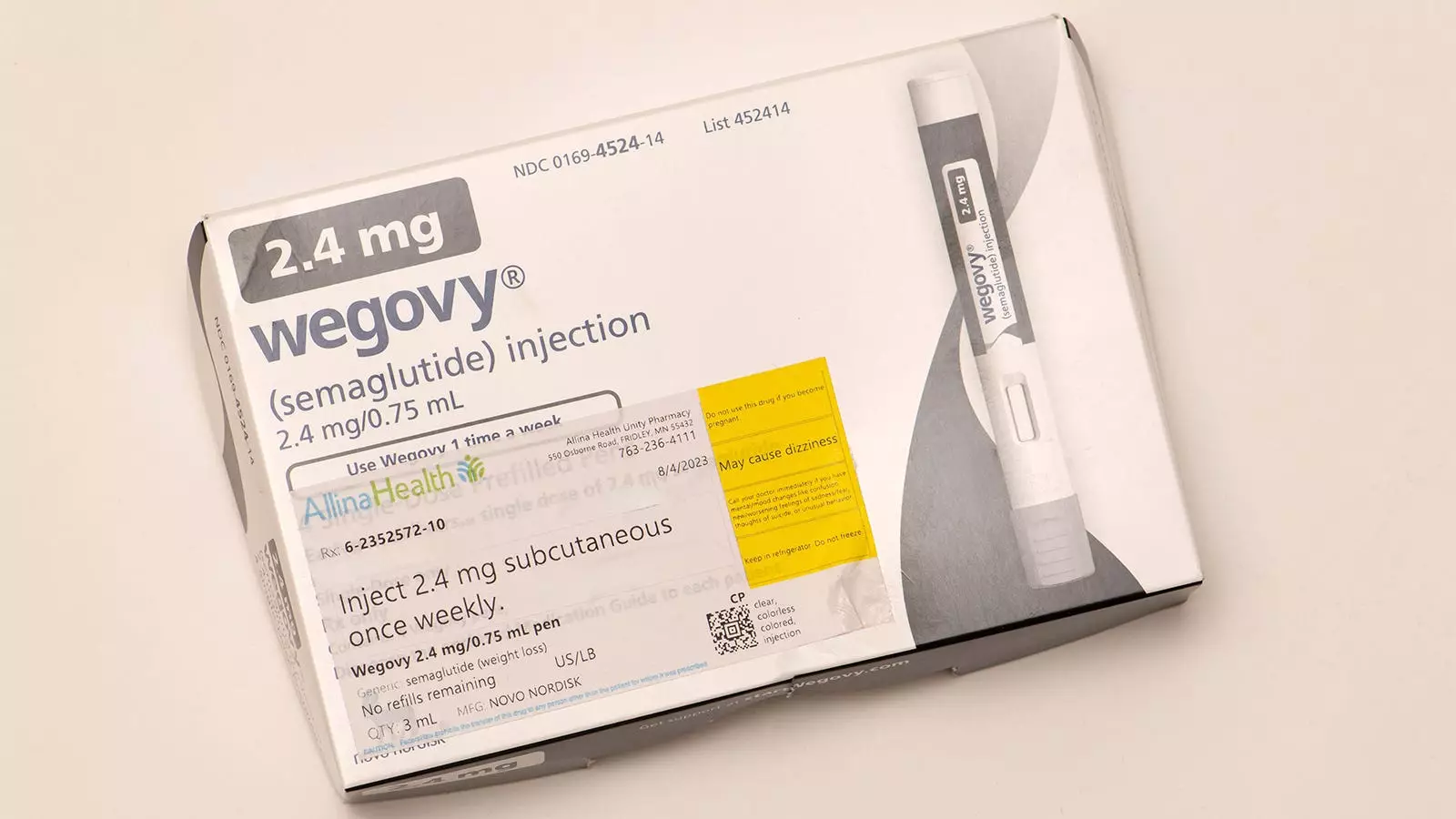

In treating adolescents with obesity, I have observed that medications like semaglutide, when combined with intensive lifestyle interventions, yield promising results. These include improved physical activity levels, enhanced body image, better sleep quality, and greater self-confidence. Such outcomes reflect the multifaceted benefits of these treatments beyond just weight loss, highlighting their potential in addressing obesity-related health risks holistically.

However, the status of treatment options for younger children—defined as those under the age of 12—has been starkly different. Historically, there have been no FDA-approved pharmacological interventions for this age group, despite the severe implications of obesity-related conditions such as prediabetes, fatty liver disease, and sleep apnea. This gap in treatment options has left many children without adequate therapeutic avenues, which is a point of frustration and concern for practitioners like myself.

Prospective FDA Approval of Liraglutide

Recent developments indicate a potential shift in this landscape. The FDA is currently reviewing liraglutide for use in children ages 6-12 with severe obesity. This consideration follows a pivotal trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine that assessed liraglutide’s effectiveness alongside lifestyle intervention. The results of this study were encouraging—children in the liraglutide group exhibited a statistically significant reduction in BMI compared to those receiving only behavioral intervention.

Importantly, logistical details such as the treatment regimen, including the requirement of daily injections, must be taken into account. While the data suggested an average BMI reduction of 5.8%, the overall landscape is complicated by the likelihood of gastrointestinal side effects, which were reported in 80% of participants receiving the medication. Additionally, although some improvements in metabolic risk factors were observed, the study did not find conclusive evidence for progress in blood pressure or hemoglobin A1c levels.

Evaluating Risks Versus Benefits

As practitioners, we bear the crucial responsibility of evaluating the trade-offs between the benefits and risks of any treatment. While liraglutide may not revolutionize pediatric obesity treatment for every child, it is an important development. Benefits may include modest reductions in BMI and potential improvements in metabolic health alongside behavioral interventions. These outcomes collectively indicate a step forward in addressing obesity in children.

Conversely, we cannot overlook the associated risks. The research presents uncertainty regarding the long-term safety and effects on growth and development. Moreover, a concerning trend is the weight regain seen post-treatment; children exhibited significant weight gain in the absence of liraglutide after the treatment ended. The ongoing open-label extension phase of the clinical trial aims to provide clarity on these long-term implications, which is paramount for developing a comprehensive understanding of the medication’s overall impact.

Childhood obesity is not just a clinical problem but a social one that necessitates a tailored approach. The decision to prescribe medications like liraglutide will require careful deliberation, including in-depth discussions with families about potential benefits, risks, and the necessity of coupling medication with behavioral interventions. Ultimately, my current stance is cautious; for most cases of children aged 6-12 years, the risks still appear to outweigh the benefits.

However, the prospect of adding liraglutide to our treatment arsenal is compelling. It offers a new option for those struggling with severe obesity, reminding us of the importance of continuous research and adaptation in the management of pediatric obesity. As the medical community makes strides toward better understanding the long-term implications of these medications, I remain optimistic yet cautious in our approach.

The critical task before us is to ensure that children do not fall behind in our efforts to combat obesity. As an advocate for evidence-based practice, I look forward to the insights that further studies will provide regarding the long-term efficacy and safety of liraglutide and other potential treatments. It is essential that we navigate this evolving landscape judiciously, protecting the health and well-being of our youngest patients as we embrace pharmacological advancements in obesity treatment.

Leave a Reply