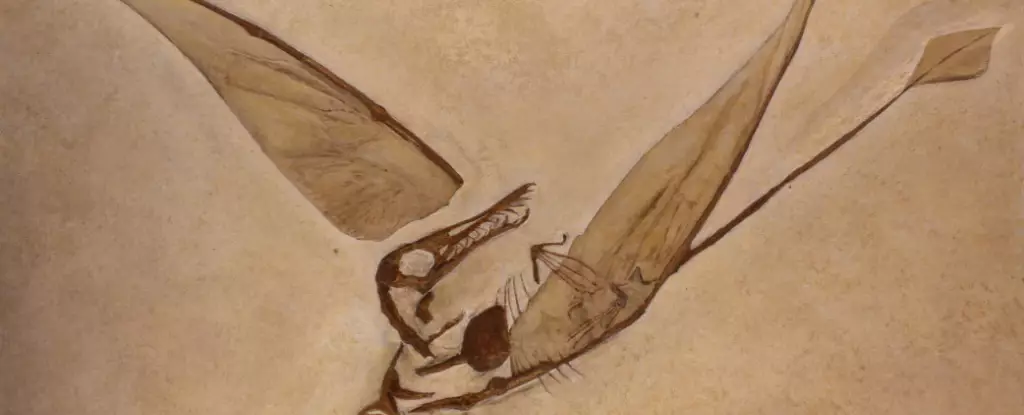

Pterosaurs, ancient flying reptiles that existed about 215 million years ago, were the first vertebrates to take flight using powered flight. Despite their similarities to birds and bats, pterosaurs were a separate branch of the reptile family tree, evolving from rabbit-like creatures. Their ability to fly set them apart from dinosaurs, with whom they coexisted.

While feathers and hollow bones undoubtedly played a role in pterosaur flight, new research suggests that a lattice-like structure in their tails was crucial for achieving flight. This structure prevented their broad-ended tails from fluttering in the wind, providing stability and control during flight. By stiffening the tail vane with a rod-like lattice structure, pterosaurs were able to reduce drag and stabilize their flight, ultimately paving the way for evolutionary success in the realm of vertebrate flight.

One of the challenges in studying pterosaurs is their rarity in the fossil record due to the degradation of their thin and hollow bones over time. However, recent discoveries of well-preserved soft tissue structures in pterosaur fossils have provided valuable insights into their flight mechanisms. By analyzing specimens that fluoresced under UV light, researchers were able to uncover hidden anatomical details that shed light on how pterosaurs achieved flight.

The study of pterosaur tail vanes revealed a cross-linked lattice of thick vertical rods and thin fibers that maintained stiffness and stability during flight. This innovative structure likely evolved from a single contiguous structure, differentiating pterosaurs from birds and bats. Furthermore, the presence of “fleshy folds” at the end of the tail vane suggests similarities to cetacean flukes, indicating a convergence in flight adaptations across different species.

In addition to the tail vane, pterosaurs utilized a tendon called the propatagium to control flight take-off and landing. This structure stretched along the leading edge of the wing, altering airflow to maneuver effectively in the sky. While birds and bats also have a propatagium, the unique oar-like tail vane of pterosaurs set them apart in terms of flight adaptations.

The discovery of the lattice-like structure in pterosaur tail vanes has provided valuable insights into the evolutionary mechanisms of vertebrate flight. By studying well-preserved soft tissue in fossils, researchers have been able to unravel the mysteries of pterosaur flight and uncover the unique adaptations that allowed these ancient flying reptiles to dominate the skies millions of years ago.

Leave a Reply